About !

TransgenicNews is a dedicated, commercial-free platform delivering authoritative coverage of the rapidly evolving field of transgenic sciences. The website primarily focuses on media reports related to transgenic animals, offering curated news and insights for professionals, researchers, and the broader scientific community. While agricultural biotechnology and GMO crop developments are not its central theme, select articles may be featured when they offer novel perspectives or relevance to broader transgenic advancements.

In addition, Transgenic.News actively highlights transformative developments in modern biology, human genomics, and human transgenics. The platform aims to inform the public with well-sourced content covering cutting-edge research, emerging applications, ethical discussions, and the ongoing evolution of genetic engineering across biomedical domains.

What is Transgenic Technology ?

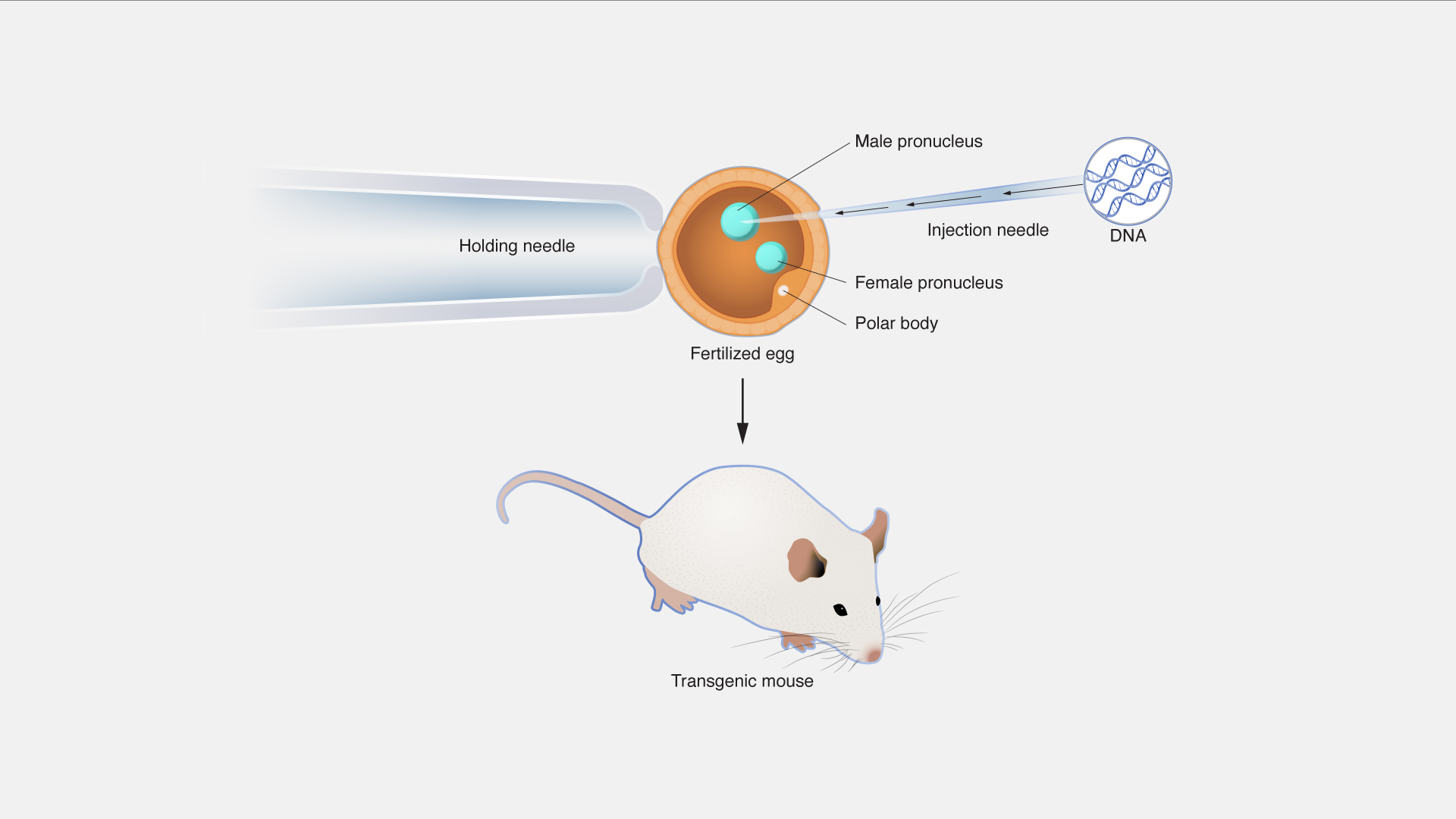

Transgenic technology involves the deliberate modification of an organism’s genome by introducing foreign DNA to achieve desired traits. This cutting-edge field, encompassing transgenic animals, gene editing, and antibody production, is transforming biomedical research, genetic engineering, and biotechnology. From developing transgenic mice for disease modeling to producing recombinant proteins, transgenic technology drives innovation in science and medicine.

Our mission is to provide researchers, scientists, and biotech companies with advanced transgenic solutions, leveraging tools like CRISPR, transgenic mice models, and monoclonal antibody production to accelerate discoveries.

Learn More About Our Transgenic Services

Custom Transgenic Animal Models

Tailored transgenic mice and other models for specific research needs.

Advanced Gene Editing

Utilizing CRISPR/Cas9 for precise genetic modifications.

Monoclonal and Polyclonal Antibody Production

High-yield, high-specificity antibodies for therapeutic and diagnostic applications.

Comprehensive Support

From project design to delivery, we guide you through every step.

Transgenic Animals: A Cornerstone of Genetic Research

Transgenic animals, such as transgenic mice, rats, and rabbits, are critical for studying gene function and modeling human diseases. By inserting or modifying genes, researchers can simulate conditions like cancer, cardiovascular diseases, and neurodegenerative disorders. Our transgenic animal services provide custom models tailored to your research goals.

CRISPR and Gene Editing: Precision in Genetic Engineering

CRISPR gene editing has transformed genetic engineering by allowing precise modifications to DNA. This technology is used to create transgenic organisms, correct genetic mutations, and develop targeted therapies. Explore our CRISPR services to see how we can support your research.

Antibody Production with Transgenic Technology

Transgenic animals are pivotal in producing monoclonal antibodies and recombinant antibodies for therapeutic and diagnostic purposes. Our advanced platforms ensure high-quality antibody production for applications in immunotherapy, diagnostics, and research. Visit our antibody production page for more details.

Get Started with Transgenic Solutions Today

Transgenic animals are pivotal in producing monoclonal antibodies and recombinant antibodies for therapeutic and diagnostic purposes. Our advanced platforms ensure high-quality antibody production for applications in immunotherapy, diagnostics, and research. Visit our antibody production page for more details.